Unveiling the world of mosquitoes: A guide

Mosquitoes are one of the deadliest animals in the world, killing close to one million people a year by transmitting about 100 different diseases – including malaria, yellow fever, Zika, West Nile virus, Chikungunya, and dengue.1,2

The three culprits: Aedes, Anopheles, and Culex

There are over 3,000 species of mosquitoes and of these, mosquitoes in three genera are particularly important in spreading disease to humans.3,4

Anopheles: Found worldwide (except Antarctica), Anopheles mosquitoes are infamous for transmitting malaria.5

Culex: The most widespread mosquito species worldwide, Culex mosquitoes can transmit encephalitis, West Nile virus, and lymphatic filariasis.6

Aedes: Flourishing in warmer climates, Aedes mosquitoes are notorious for spreading diseases like Zika, Chikungunya, and dengue.7

Aedes aegypti versus Aedes albopictus

Two species of Aedes mosquito: aegypti (originating from Africa) and albopictus (from Asia) are responsible for spreading dengue.8-10 Despite being of the same species, they have distinct differences.11 Aedes albopictus, also called Asian tiger mosquito, is a more aggressive biter and prefers to bite during the day.11 Aedes aegypti, while also mainly biting during the day, is stealthier, often targeting the ankles and elbows, and has a strong preference for biting humans over other mammals.12 Aedes aegypti also prefers to live and breed close to, or in, human households, whereas the habitats for Aedes albopictus are diverse: besides indoor environments, they can also include fields and forests.13,14

Geographically, the distribution of Aedes aegypti is limited to tropical and subtropical regions but Aedes albopictus also appears in warm and cold temperate regions – it is established in a number of European countries.9,15

Aedes aegypti is the primary spreader of dengue but the role of Aedes albopictus should not be understated9,12

Female mosquitoes and disease transmission

Female mosquitoes do all the lifting when it comes to spreading diseases to humans: it is only the females that feed on animal blood (including human), the males do not bite, they only feed on flower nectar and plant juices.16 In their quest to reproduce, the female mosquitoes of some species use needle-like proboscis to pierce the skin of various mammals, humans included.17,18 This act of feeding, accompanied by the injection of saliva, can not only trigger swelling and itching but also transmit diseases, such as dengue.17-20

When infected with the dengue virus from a mosquito bite, individuals may develop a wide range of symptoms, including some that can lead to serious complications.19 Approximately 1 in 4 dengue infections are symptomatic, and of these, about 1 in 20 can progress to life-threatening severe dengue.21 Read more about the symptoms of dengue here.

Dormant Vectors

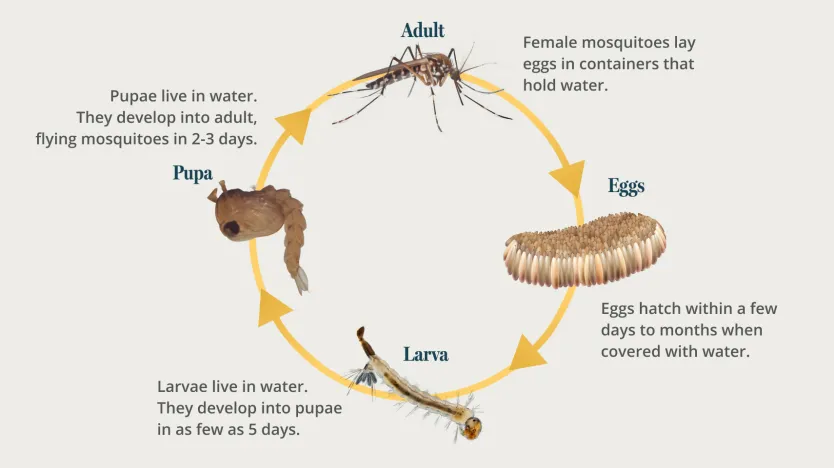

After feeding on blood, the female lays her eggs – up to 200 at a time – inside a container just above the water line.13,22 In fact, an area as small as a coin is all the water she needs for this.23

“Mosquitoes only need a small amount of water to lay eggs. Bowls, cups, fountains, tires, barrels, vases, and any other container storing water make a great “nursery””

– Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)13

The laid eggs stick to the wall containers like glue.13 They are resistant to drying, and can survive dormant for months, if needed, until conditions are right (such as contact with water from a sprinkler or rain) for them to hatch.13

Aedes mosquitoes grow very quickly, from eggs to adults

The hatched eggs give way to highly active larvae or “wigglers” that feed on particles in the water.13,24,25 Like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly, the mosquito larvae form a case called a pupa, which transforms into a flying mosquito.25

Mere moments: The entire lifecycle of Aedes mosquitoes takes 8– 10 days13

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)13

Climate change is creating the ‘perfect storm’ for disease-carrying mosquitoes

Many mosquito-borne diseases are sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature and humidity.26 Raised temperatures can both accelerate mosquito reproduction and development while higher humidity can extend the mosquito’s lifespan.27 In addition, increased rainfall can provide more potential breeding sites (standing water) for mosquitoes.28 Read more about the impact of climate change on the spread of dengue here.

A warming world is extending the reach of dengue-carrying mosquitoes29

Urbanization is as important as ever to dengue-carrying mosquitoes

For the past 5,000 years, there has been a close association between settled human societies and Aedes aegypti.8 These mosquitoes have adapted to breed in artificial containers and developed a preference for human blood.8 Today, urbanization continues to help fuel the spread of dengue.30 Urban environments provide an abundance of man-made containers for the mosquitoes to breed in while dense populations allow for rapid virus transmission.30 Additionally, unplanned urbanization often results in poor infrastructure, such as inadequate water drainage and waste management systems, which mosquitoes readily exploit.30

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fighting the World’s Deadliest Animal. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/stories/world-deadliest-animal.html. Accessed January 2024.

Keller MD, et al. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20936. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/srep20936. Accessed January 2024.

Dahmana H, Mediannikov O. Pathogens. 2020;9(4):310. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/9/4/310. Accessed January 2024.

Cantillo JF, Puerta L. Front Allergy. 2021;2:690406. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/falgy.2021.690406/full. Accessed January 2024.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/biology/index.html Accessed January 2024.

Nchoutpouen E, et al. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(4):e0007229. Available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0007229. Accessed January 2024.

Flores HA, O'Neill SL. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(8):508-518.

Rose NH, et al. Elife. 2023;12:e83524.

Oliveira, S, et al. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9916.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Aedes albopictus - Factsheet for experts. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/facts/mosquito-factsheets/aedes-albopictus. Accessed July 2024.

Madariaga M, et al. Braz J Infect Dis. 2016;20(1):91-8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dengue and the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Available at: https://health.hawaii.gov/docd/files/2015/11/CDC_aegypti_factsheet.pdf Accessed July 2024.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Life Cycle of Aedes Mosquitoes. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/about/life-cycle-of-aedes-mosquitoes.html. Accessed July 2024.

Cui G, et al. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):568.

Kramer IM, et al. Sci Total Environ. 2021;778:146128.

National Environment Agency. Singapore. Wolbachia-Aedes Dengue Supression Strategy. Available at: https://www.nea.gov.sg/corporate-functions/resources/environmental_health_institute/wolbachia-aedes-mosquito-suppression-strategy/male-mosquitoes-do-not-bite. Accessed July 2024.

What is a Mosquito?. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/about/what-is-a-mosquito.html. Accessed January 2024.

Dixon AR, Vondra I. Materials (Basel). 2022;15(13):4587. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/15/13/4587. Accessed January 2024.

World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue. Accessed November 2023.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. General Information about Mosquitoes. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/mosquitocontrol/general-information-about-mosquitoes. Accessed November 2023.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Features of Dengue. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/hcp/clinical-signs/index.html. Accessed July 2024.

Gunara NP, et al. Sci Rep. 2023; 13,17395.

National Environment Agency. Singapore. Stop Dengue now. Available at: https://www.nea.gov.sg/dengue-zika/stop-dengue-now. Accessed July 2024.

Souza RS, et al. Front Physiol. 2019;10:152

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Mosquito Life Cycle. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/mosquitocontrol/mosquito-life-cycle. Accessed November 2023.

Ahmed T, Hyder MZ, Liaqat I, Scholz M. Climatic Conditions: Conventional and Nanotechnology-Based Methods for the Control of Mosquito Vectors Causing Human Health Issues. Int J Environ Res Public Health.2019;16(17):3165.

European Climate and Health Observatory. Dengue. Available at: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/observatory/evidence/health-effects/vector-borne-diseases/dengue-factsheet. Accessed July 2024.

Rocklöv J, Dubrow R. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(5):479-483.

Laporta GZ, et al. Insects. 2023;14(1):49.

Gubler DJ. Dengue, Urbanization and Globalization: The Trop Med Health. 2011;39(4 Suppl):3-11.