Seasons may shift dengue rates: but dengue remains a year-round threat

There is seasonal variability of dengue throughout the year in some areas of the globe. Outbreaks are often related to the climate, as this can directly increase the dengue-carrying (or Aedes) mosquito numbers.1

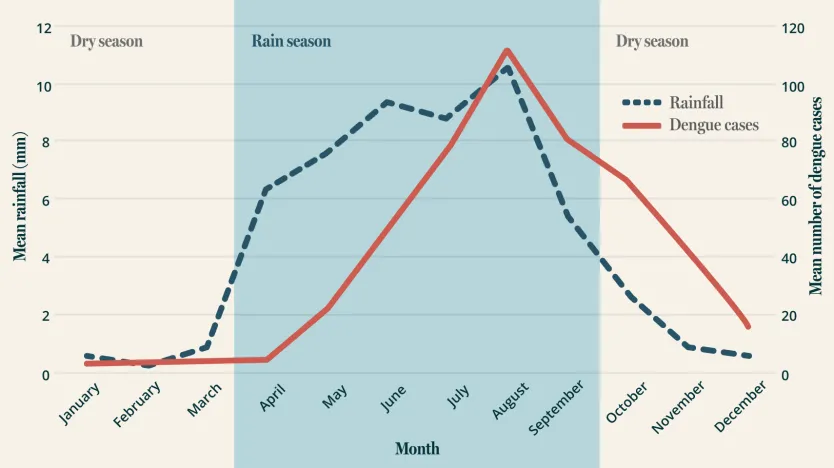

It's all in the timing: dengue cases rise during rainy season

Dengue outbreaks are most likely during the rainy or monsoon season, as most dengue epidemics occur during wetter and warmer months.2,3 Rainy season coincides with peaks in numbers of baby dengue-carrying mosquitoes.3

Changes in temperature and rain across the year impact the speed at which Aedes mosquitoes grow.1 Not only that, but more rain also provides more places for mosquitoes to live and breed.1

Research has shown patterns in dengue cases change during the year, linked to the seasons. A high number of rainy days and high humidity can provide the perfect setting for an increase in reported dengue cases.3,4 As a result, dengue cases can spike or increase sharply during rainy season compared to other times of the year.2,4 The increased number of dengue cases that occur during the rainy season can sometimes lead to outbreaks – a situation where the sheer numbers of cases are so much higher than seasonal peaks that they overwhelm healthcare systems.5,6 But, along with these rainy season peaks, there is a consistent threat of dengue infection throughout the rest of the year too (though the threat can be higher during rainy season).2,4,7 For instance, in parts of Vietnam, while 72% of dengue cases occur between the wetter months of June and November, the remainder occur outside this period.4

Adapted from Morales et al. 2016

Although rates of dengue vary throughout the year, the risk of being infected is always present in endemic regions.2,4

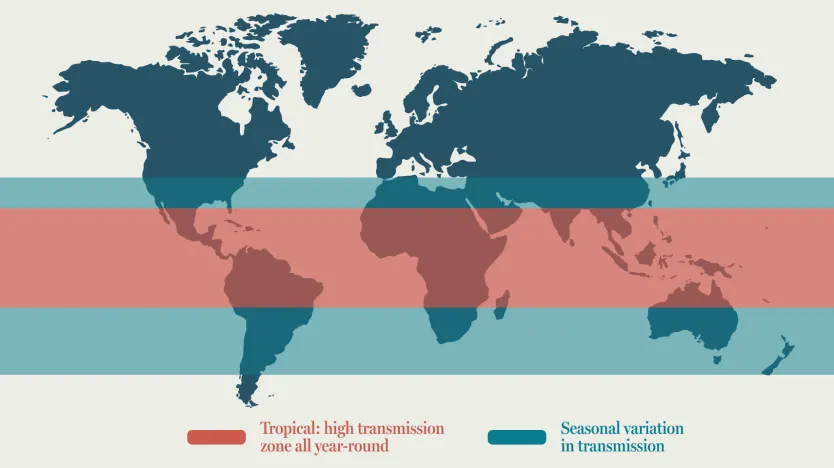

A global situation

Currently, areas within the tropics are prone to the spread of dengue all year round. Yet, the areas surrounding the tropics generally see more seasonal variation in the rates of dengue. As the world gets warmer, it is likely that dengue will continue to spread across the globe.8,9 Rising temperatures can increase Aedes mosquito numbers by boosting their survival and growth.9

Adapted from Morin C, et al. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022

On guard against dengue

Since the rates of dengue in endemic areas can vary with seasons, it might seem that there is no need for protective measures during the cooler and drier months. However, this could be a mistake; in some endemic regions dengue is a real threat all year round.2,4

Endemic countries are often hot, humid and wet, allowing Aedes mosquitoes to thrive (and spread dengue) year-round.10 For example, the ideal temperature range for mosquito survival and dengue virus incubation is 18°C to 31°C.11 Dengue endemic countries, such as Fiji constantly have temperatures within this range.10 Also, the lowest humidity level that Ae. aegypti mosquitoes can survive is 60%; the mean humidity in many countries remains well above this – Sri Lanka for instance, has an average humidity of around 80%.11 Keep in mind though, dengue cases are still likely to peak when conditions are the most suitable for mosquitoes.4 So, it is important to remain especially vigilant during these times, with prevention measures like mosquito control and bite avoidance.

The cooler temperatures of some countries prevent them from becoming dengue endemic with year round transmission.12 In Japan, winter is too cold for mosquitoes to survive and spread dengue; January is the coldest month in Tokyo, and average temperatures fall between 3°C–9°C.12,13 That said, temperatures in August (the hottest month) range between 25°C–30°C which do support Ae. aegypti mosquito survival and the spread of dengue.11,13 However, be aware, that more and more areas of the world are becoming suitable for mosquitoes, so a global effort is needed to minimize the spread and consequences of dengue.14

References

Zhang Q, et al. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e024197.

Morales I, et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94(6):1359-61.

Wongkoon S, et al. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138(3):347-53.

Do TT, et al. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1078.

Cousien A, et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(12):2281-2283.

Brady OJ, et al. Epidemics. 2015;11:92-102.

Pasin C, et al. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0207878.

Morin C, et al. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022; 17:064042.

Yuan HY, et al. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4297.

Filho WL, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):5114.

Abdullah NAMH, et al. One Health. 2022;15:100452.

Lee JS, Farlow A. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):934.

Weatherspark.com. Available at: https://weatherspark.com/y/149405/Average-Weather-at-Tokyo-Japan-Year-Round. Accessed November 2023.

Liu-Helmersson et al. J, Environ Res. 2019;172:693-699.